Eva Moreno Galbis, 2020, European Economic Review, vol. 130

RESEARCH PROGRAM

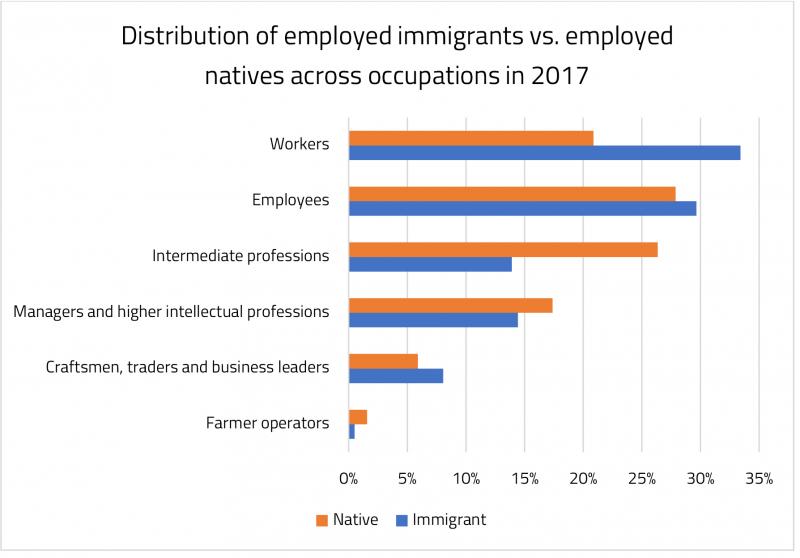

In France, more than 62% of professional injuries concern manual workers. With over 41 professional accidents per million hours worked, the construction sector stands out as the most dangerous economic activity. On average, more than 33% of immigrants are allocated to manual work (compared with less than 21% of natives), and this rises to over 50% for immigrant men. Immigrants represent around 10% of the total employed population in France, but they are over-represented in the construction sector, where they constitute more than 23% of all workers. They also tend to become houseworkers (33%) and security guards (25%). Why are immigrants over-represented in riskier sectors and more strenuous occupations? What pushes them to accept less desirable working conditions?

Calculation from author based on French Labor Force Survey, 2017

PAPER’S CONTRIBUTIONS

There are several credible explanations for immigrants’ greater willingness to accept riskier jobs than their native counterparts. First, because their home country working conditions may be very hard and they may also have experienced very difficult conditions during migration, immigrants are likely to perceive risk differently from natives. Second, lower levels of education and social capital or poor language proficiency may make immigrants less informed about the actual risks associated with a job. Third, newly arrived immigrants tend to be in better health than natives, so they might be willing to take more physically strenuous jobs. Finally, even if immigrants and natives have similar knowledge about job risks and the same legal status, immigrants might still hold riskier jobs than natives because of differences in outside opportunities (value of leisure, alternative employment opportunities or differences in unearned income).

Our paper focuses on two particular factors: unearned income (i.e. wealth, value of leisure, home production, etc.) and individual preferences (driven by sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, age, education, marital status, children, etc.). The paper develops a circular model in which each individual has a preferred position in the circle of available working conditions. However, the individual may be willing to accept a range of working conditions. The framework predicts that the range of acceptable working conditions decreases with unearned income and with the utility loss induced by the distance between an individual’s most preferred and actual working conditions. If natives have higher unearned income than immigrants and experience a higher utility loss from the gap between the most preferred and actual working conditions, the range of acceptable working conditions will be larger for immigrants than for natives. This implies that immigrants will put up with relatively worse working conditions than natives with respect to their most preferred choice.

Our framework also predicts that flexible wages reduce the difference between natives’ and immigrants’ working conditions, since both wages and working conditions can be used as adjustment variables in bargaining between firms and workers. In contrast, rigid wages induce larger immigrant-native gaps in working conditions by becoming the only adjustment variable.

The model’s predictions are tested on French data over the period 2003-2012. We propose three alternative indicators that proxy outside employment opportunities: (i) home ownership; (ii) the implicit subsidy received by tenants in social housing with controlled rent; (iii) the expected social insurance benefit the employed individual will receive in the event of job loss.

To control for differences in preferences over working conditions across nativity groups driven by differing demographic composition, we propose a counterfactual weight approach consisting of imposing yearly an identical composition in terms of gender, age, education, civil status (i.e. married or not) and children for immigrants and natives.

Three major conclusions (consistent with theoretical predictions from the model) are drawn: (i) the average immigrant-native gap in working conditions is larger in the presence of rigid wages; (ii) high unearned income is associated with better working conditions; (iii) demographic characteristics explain a proportion of the immigrant-native gap in working conditions through their effect on preferences. This particularly applies to minimum wage earners with high unearned income.

FUTURE RESEARCH

While most of the economic literature has studied job content in terms of tasks, wages or physical risks (injuries and illness), our future research will focus on non-pecuniary working conditions such as hours, flexibility, mobility, future perspectives, autonomy, support or psychological risk (including harassment). We plan to analyze how the spread of digital technologies has modified these work dimensions, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gender issues will be prominent in this research agenda. Digitalization has changed the range of jobs that women find desirable relative to men, via changes in non-pecuniary working conditions. For example, physical strength has become less important in some jobs, but there has also been an increase in the demand for so-called “male working conditions” – such as long hours, unusual working hours or geographic mobility. The overall impact of digital technologies on occupational sorting by gender, on women’s job satisfaction and on women’s labor market attachment is thus uncertain.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Summer 2021.