Liam Brunt & Cecilia García-Peñalosa, 2022, The Economic Journal, 132 (642), 512-545

Urbanisation and technological progress are closely linked. Economic historians and development economists have widely documented how workers are drawn to cities from the traditional sector in order to profit from the modern technologies that are created and adopted there. Models of long-run growth thus tend to see urbanisation as a consequence of economic growth. Yet a vast literature on economic geography maintains that urbanisation itself generates productivity gains. Going back to Marshall, economists have explored the idea that high density in cities results in learning – and thus in both skill upgrading and innovation. This suggests that agglomeration can cause economic growth through its impact on technological change.

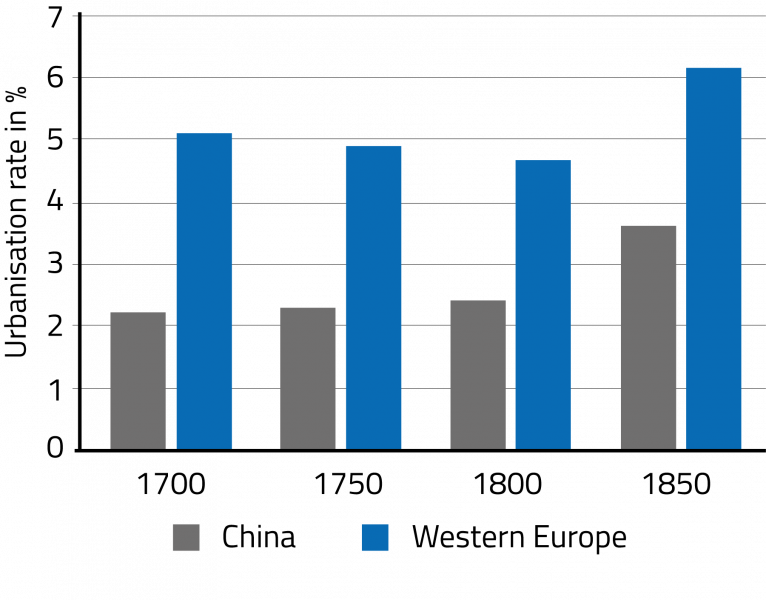

Our analysis seeks to examine the two-way relationship that can emerge between urbanisation and innovation, in order to understand how they interacted at the onset of modern economic growth. Our interest in this question is motivated by a somewhat surprising stylized fact: that Western Europe was unusually urbanised before the Industrial Revolution. Many historians regard China as the most technologically advanced country in the Middle Ages. However, despite an early upsurge in the share of the population living in cities, Chinese urbanisation rates remained low throughout the modern period. By contrast, Europe experienced a marked increase in the share of the population living in cities during the early modern period, already exhibiting an urbanisation rate of 5% by 1700, more than twice that prevailing in China, as shown in Figure 1.

Within Europe, the UK had the highest urbanisation rate. It had started to rise well before the First Industrial Revolution, tripling from 6 to 18% between 1600 and 1750, the latter date usually being considered the starting point of the Industrial Revolution. Examining the population in the four largest cities in England, Scotland and Ireland, we find that the UK experienced an urban growth spurt before 1750. Whilst the English population increased by 14%, the population of major cities, notably Liverpool, Manchester, Dublin, Glasgow and Edinburgh, doubled or tripled in size in the first half of the 18th century. Such timing raises the question of the extent to which urbanisation was a cause – rather than a consequence – of economic growth.

Figure 1. Urbanisation rates in Western Europe and China

Our paper develops a model of growth consistent with the idea that urbanisation precedes industrialisation. First, we argue that the economy consists of two sectors: agriculture in rural areas and manufacturing in cities. Manufacturing is assumed to be a traditional artisan activity rather than factory based, without the use of physical capital and with a worker’s productivity depending only on the number of ideas that he holds. As the average number of ideas available grows, manufacturing productivity increases and the incentive to leave the countryside rises, leading to higher manufacturing employment. Second, we also consider how ideas are created and transmitted. Transmission between agents occurs through imitation: individuals in cities may acquire an idea by meeting someone who already possesses it. A novel idea is created through observing the ideas of others, thus endogenously inventing new ways of production. In either case, idea acquisition results from meetings between individuals; and following Marshall, we suppose that the number of meetings is an increasing function of urban density. Under these assumptions, urbanisation becomes the determinant of manufacturing productivity.

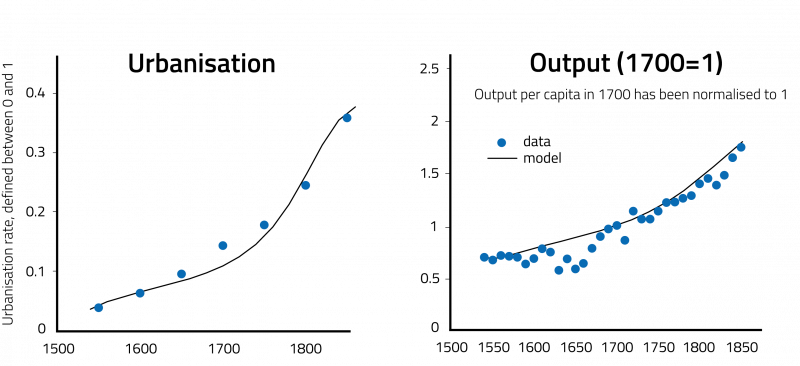

The feedback mechanism between city size and technology generates a novel set of growth dynamics. A shock to urbanisation results in knowledge creation and diffusion, higher manufacturing productivity and a flow of labour into manufacturing (and thus cities). The resulting higher urban density further increases manufacturing productivity, setting off a process of sustained growth. Our model hence makes urbanisation – as opposed to industrialization – the key element in a theory of development. Figure 2 reports the evolution of urbanisation and output in the model (continuous lines), as well as those observed in the actual data (dots). The trigger for the growth process is an exogenous shock to agricultural productivity that shifts labour into manufacturing, increasing urban density and thus raising productivity. The shock can hence create a virtuous circle, in which urbanisation and productivity keep increasing. Note that the model reproduces the acceleration in urbanization and in output that we see in the data.

These accelerations are the result of the microfounded process of knowledge generation that we postulate, which allows us to dissociate the creation of ideas from their diffusion. Ideas are invented by an individual and then transmitted to the next generation through imitation. As a result, innovations will increase productivity only slowly, as imitation by subsequent generations occurs. Thus, a key contribution of our work is that our model simultaneously delivers fast technological change and slow overall productivity growth in manufacturing, in line with existing estimates for Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Figure 2. Output and population: data and simulation results

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Summer 2022.

© Giammarco / Unsplash