By Bruno Ventelou

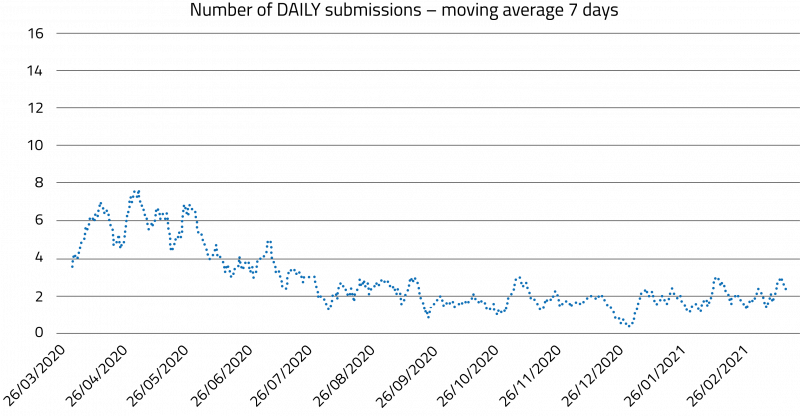

The mobilization of economists during the Covid crisis has been impressive. For example, the Covid Economics pre-print series is now on its 77th issue in one year. With six to seven research papers per issue, and a publication rate that rose to three issues per week during the peak of the crisis, this is unprecedented! (see Figure 1.)

Figure 1. One year of Covid Economics Thanks to Charles Wyplosz for providing access to this data.

This research perspective attempts to outline the mobilization. The overview will first allow us to examine how the methodology behind our discipline has advanced. Now fully recognized, it can exchange with other fields (particularly medicine) whose scientific merit has long been established. However, this survey will simultaneously look at the discipline’s position in society, which remains unstable, poorly perceived, and / or built on numerous misunderstandings.

Economic research on the Covid epidemic can be divided into four main fields. This classification is, however, neither exhaustive nor exclusive.

1/ Improved Forecasting of the Epidemic, Compatible / Conflicting Perspectives

One of the major entry points for economists in epidemiology has been to work on improving the tools for modeling the dynamics of the Covid-19 contagion as it affected the population across space and time. Since at least the 1970s—known as the “microeconomic foundations of macroeconomics” period—economics has called for individual decisions to be taken into account, so as to better predict large macroeconomic movements. In this case, the incidence of Covid in the community was the “macro-population” variable, and endogenizing the contact matrix (in SIR models, for example) was the means to improve prediction. This involves studying the behaviors of rational social actors, who “reoptimize” their risk exposure choices and partially curb the curve of contagion themselves through decisions on movement (going out vs. staying in), social participation (distancing, social “bubbles”), and self-protection (wearing a mask, preventive measures). This attempt to endogenize selfprotective attitudes toward risk may even shed light on why epidemiological models were inaccurate, overestimating contagion, especially in France during winter. In other words, microeconomic agents could readily make forecasting models lie, and they took advantage of this. The shades of the “Lucas critique” is not far off.

2/ Macroeconomics of the Crisis, Lockdown, and Restrictive Measures

This is a tradition that began with work from the 50s and 60s on the economic history of the Renaissance (with the Plague possibly offering a way out of the trap of underdevelopment presented by the economy of the Middle Ages), and went on to encompass malaria and AIDS in the 80s and 90s. The work addresses the impact of a major epidemic on the economy as well as the impact of the measures aimed at preventing the virus from spreading. Raouf Boucekkine discussed this in a previous AMSE Newsletter in 2020, which I recommend as useful reading.

What’s new about this crisis is that macroeconomic assessments have gone beyond focusing on the pandemic, also examining the national response. The macroeconomics of lockdown have virtually become a sub-discipline of economics, known as “lockdown accounting” (Gottlieb et al. 2021). Sectoral impacts, such as the housing market and transportation, have also been studied.

3/ Behavior Regarding Restrictions and Vaccines / Nudges

Another area of research in Covid economics focuses on relatively recent developments in behavioral economics. Encompassing the fields of psychology and economics, and having reached a good level of recognition after being awarded two Nobel prizes in economics in 2002 and 2017, it is only natural that behavioral economics has found itself at the forefront of research during the crisis. It took advantage of this position to “test” its major and often still fresh results, using the Covid epidemic as its laboratory. Cognitive biases, information processing, and the salience of certain events—or rather, of certain forms of communication about these events—have been the subject of considerable attention during the crisis. Furthermore, there has been a lot of interest in the role of nudges, (sometimes) tested as an alternative to classic economic incentives to guide agents’ prophylactic behaviors. Governments that implemented “nudge units” have seen the beginnings of a return on their investment.

I believe that behavioral economics is just beginning its alliance with public health, for which it has only been producing results for the past decade (Loewenstein at al., 2013). One indisputably promising field examines how agents adhere to preventive measures and, particularly, to vaccines. Two main avenues of such determinants are explored. One examines how social norm nudges improve compliance with preventive measures and vaccines (Bilancini et al., 2021), while the other examines the cognitive biases in risk perception and probability processing, which are the source of the nudge strategies, particularly to determine to what extent agents accept vaccines.

4/ Since “Classic” Approaches in Health Economics were Developed for Every Disease, why not for Covid, too?

Any discussion of the economic analyses of Covid would be unbalanced if it didn’t consider the most standard convergence between economics and health, namely, the economics of the medical sector and its allocative choices. Medico-economic approaches can shed light on the cost-benefit tradeoffs of fighting against the Covid-19 epidemic. In stark contrast with the usual medico-economic calculation, the “treatment inflicted” this time was of a non-medicinal nature and involved losses of economic activity, to be calculated outside the healthcare system, with tools that left a considerable margin of uncertainty.

In any case, comparing these estimated losses against the number of lives saved gives the impression that the implicit price of human life can be calculated on the basis of the governmental choices made regarding Covid. This implicit price is similar to the economic value of human life generally accepted for other diseases (cancer, etc.), which acts as a criterion of limits when investing in healthcare systems (for systems that officially accept that health - life years gained - and money are commensurable). However, it is arguably too soon to develop this theory ex post. Yet decisions on public policy were based on notably unreliable forecasts with numerous errors of assessment, rather than any well-anticipated calculation of the number of lives to be saved, or even of intensive care capacity to manage. It all came down to playing it by ear. The criterion of capacity nevertheless raises significant ethical questions: what are the underlying tradeoffs between the dimensions of well-being? And the trade-offs between people?

Another classic health economics topic that arose around Covid-19 was the social gradient of the disease (Bajos et al. 2020). Social determinants that affect the disease’s outcome include exposure to the virus at the workplace (not everyone can work remotely), the use of public transportation rather than a private car, the greater risk of severe forms of Covid-19 (the social gradient further affects aggravating comorbidities), and consequences of the health crisis on living conditions (such as income loss for small businesses or the self-employed). Other factors, like access to healthcare for chronic or mental illnesses, can also be affected – the experience of lockdown differs according to the nature and size of housing.

Summary & Assessment

This analysis, arbitrarily divided here into four parts, is still pretty recent. With greater hindsight, some of the points currently identified as major may change. Nevertheless, a provisional conclusion can be drawn. For a problem that appeared only a little over a year ago, the amount of Covid-related output generated by economists is already impressive. However, it should be recognized that economics is not doing it alone — almost every discipline has waded in (obviously, this is in addition to the fields of medicine and public health, which immediately and visibly mobilized against Covid). A good example is the article by Bavel et al. (2020), which goes beyond economics to encompass the concerns of the social sciences.

Interdisciplinarity has undoubtedly been facilitated by the empirical turn taken by economics, which has adopted the use of randomized trials and experimental economics as well as econometric and data science techniques. The quarrels and great debates of the 1970s and 1980s (such as classical vs. Keynesian economics), although probably a prerequisite to developing a solid body of knowledge, were unlikely to be directly useful to public health decision-makers. The economic output of recent years, derived from extensive empirical evaluation, has brought economists closer to the experimental sciences and to the production of applied and applicable research results that can be useful in medicine and elsewhere.

A less positive observation might be that decisionmakers and the general public have primarily observed and retained items 2 and 4 of this overview, in which economists are seen as “bearers of contradiction” to physicians and epidemiologists, because economists point out the economic and social costs of decisions.

Contrastingly, the position taken here is to stress the role that economic analysis can play when aligned with public health approaches (as in items 1 and 3), enhancing the effectiveness of these approaches without necessarily opposing them or introducing another opposing motive, such as maintaining GDP. Economics has something to say, even when its (sole?) objective is that of saving lives. There is a glaring absence of economists on the Covid scientific advisory committee, the excuse being a desire to avoid suggesting that economics reasoning might have influenced its recommendations. However, even when their sole objective is to save lives, economists are worth listening to. And that is something not fully recognized by the medical profession, nor perhaps by society either.

References

Bajos N. et al., October 2020, “Les inégalités sociales au temps du Covid-19?” Questions de santé publique, 40.

Bavel J.J.V., Baicker K., Boggio P. S. et al., 2020, “Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response”, Nature Human Behavior, 4, 460–471.

Bilancini E., Boncinelli L., Capraro V., Celadin T., & Di Paolo R., 2020, “The effect of normbased messages on reading and understanding COVID-19 pandemic response governmental rules”. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy, vol. 4(S), 45-55.

Gottlieb C., Grobovšek J., Poschke M. & Saltiel F., 2021, “Lockdown accounting“, The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, In press.

Loewenstein G., Asch D. A. & Volpp K. G., 2013, “Behavioral economics holds potential to deliver better results for patients, insurers, and employers”, Health Affairs, 32(7), 1244-1250.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Summer 2021.