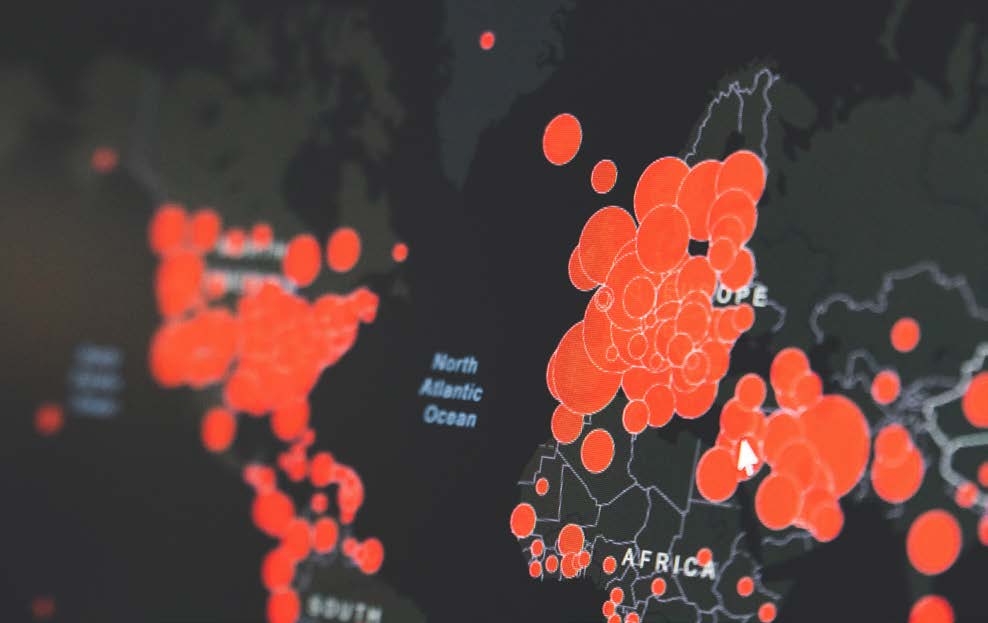

Raouf Boucekkine, researcher in economics at AMSE, offers a perspective on the economics of epidemics and on some of the new challenges this discipline must now confront to help address the Covid crisis.

The COVID-19 crisis is currently inspiring a huge number of urgent papers and research projects worldwide, in several disciplines. Many economists have discovered the standard structure of epidemiological models and associated totemic objects like the famous R0 (i.e, basic reproduction number of an infection). A good friend of mine, a well-respected econometrician, commented to me that he would never have suspected that these models were so simplistic before the COVID-19 tsunami of papers! It’s true that when Susceptible – Infected – Recovered (SIR) or Susceptible – Exposed – Infected – Recovered (SEIR) models are applied to the current avalanche of new issues raised by COVID-19, the standard mathematical epidemiology models don’t look so good. But we should remember that this is the first time that so many economists with no background in health economics have come face to face with the underlying epidemiological « fundamentals », as the current pandemic has grown increasingly puzzling.

Indeed, with quite a few exceptions (mainly related to malaria, see e.g Chakraborty et al, 2010), most economists previously modelled epidemiological shocks merely as transitory, and far less enduring, mortality/morbity shocks. In the best case, the precise age profile of mortality is accounted for. That’s what I’ve been doing for more than 15 years, never looking or even thinking of looking, at hospitalisations and/ or infection dynamics. I think this is largely because researchers who came to this area because of AIDS (like me) or Ebola in Africa, quickly figured out that if any data makes some sense in this continent to track these major epidemics, it’s mortality data. But COVID-19 is a completely different ball game: mortality is just one important statistic among others potentially available. Regarding certain issues like the optimal design of quarantines under health system capacity constraints, it is clearly less important than the number of patients in intensive care units, for example. In this sense, COVID-19 is triggering a revolution in this area of economic research. I have never seen so many truly economic (or econometric) epidemiological models at once.

Epidemics and the economics of disasters

Indeed, the classical appraisal of the economic impact of epidemics belongs to what we could label the economics of disasters. Probably one of earliest and most famous works in the field is that of Jack Hirshleifer (1966) on the Black Death (1348-50). Among several interesting conclusions, including the role of the Black Death in the demise of feudalism, he addressed quite a serious consideration: « Direct inferences can hardly be drawn from this 14th century catastrophe as to possible consequences of thermonuclear war... » (page 40). The report was commissioned in the mid-60s.

The analogy between wars and epidemics is made in much more recent publications and even textbooks. In chapter 5 of the economic growth textbook of Barro and Sala-i-Matin (1995), both wars and epidemics are described as departures from the equilibrium value of the human to physical capital ratio. An epidemic (resp. a war) is associated with relative scarcity of human (resp. physical) capital. In two-sector models à la Lucas-Uzawa, growth is driven by human capital accumulation, and the education sector is more human-capital-intensive. Accordingly, and contrary to wars, which are followed by neoclassical catching-up transitions (« miraculous growth »), the economies hit by epidemics recover much more slowly because of the relative scarcity of human capital (the engine of growth), inducing high operation costs (as wages go up) in the education sector. The analogy between wars and epidemics then breaks down.

What about health ?

The above formalisation of epidemic shocks leaves no room for a supposedly related central concept, health, and its companion, health policy, even though economic theory has been perfectly equipped to deal with it since the early 70s and Michael Grossman’s work on health capital. One of the reasons for this early trend is that many researchers focused on short-lived epidemic episodes like the Spanish flu or the Black Death (at least its main wave). Both were long considered as shocks either on the initial human to physical capital ratio or on exogenous survival rates for one period or so. Behind this approximation, there is the belief that such « sudden » and « short» shocks will induce an unavoidable upsurge in mortality in the short-run and no long-term effect. It is only very recently that novel hypotheses like the fetal origins hypothesis have underlined the importance of the initial health endowment, thus strongly undermining the above-mentioned beliefs. Along with the fetal origins hypothesis, several cohort studies have identified specific long-term health effects of the Spanish flu « sudden » shock (see e.g Almond and Mazumder, 2005). But the fact remains that health expenditures (private or public) and health policy and systems did become central earlier with the emergence of one enduring epidemic, AIDS. Tens of papers have been devoted to the evaluation of the short- versus long-term effects of AIDS, and the inherent (optimal) prevention/treatment public policies. More interesting probably by far than other epidemics before (at least in terms of the variety of questions raised), AIDS has inspired a dense literature on economic behaviour in response to epidemics. This includes compliance with prevention measures (e.g, use of condoms), and health spending, saving, schooling and reproduction behaviours under AIDS (see e.g Boucekkine et al.,2009). This behavioural dimension of economic research on epidemics is likely to be even more important with emerging diseases.

These emerging diseases are challenging

While uncertainty and risk are inherent in any epidemic, even the most studied and best characterised ones, the uncertainty and risk involved in the diseases emerging since the beginning of the century are particulary challenging. A key common factor is that many of these diseases are caused by respiratory viruses. Just like the Spanish flu one century before, their contagiousness can be formidable, as it is linked to the vital act of breathing (unlike vector-borne diseases such as malaria). We all recall the H1N1 virus a decade ago and the panic it caused in autumn 2009 in France (and the famous massive vaccine order by former Health Minister Bachelot). The current COVID-19 epidemic is a major source of uncertainty both for individuals and for the authorities, as its basic epidemiology is not yet understood in many respects. While quarantines seem to be useful in slowing down epidemic diffusion, their economic cost is huge. And the question of optimal design of quarantines (duration included) with or without (grouped or not) testing is extremely tricky, given the extent of the uncertainty.

Not to mention the obvious moral hazard problems: individuals confined (or subject to any kind of constraint) might not believe they are equally at risk of infection and might not comply with the rules despite penalties. This is probably true of many (infected) asymptomatic individuals, one of the peculiarities of COVID-19, especially the youngest. Of course, they, like the authorities, do learn over time: for example they learn whether confinement is making an impact on the epidemic, through the publication of daily statistics. But if information distribution is curbed, the moral hazard problem becomes more acute. What should the authorities announce at that stage, other than the typical warnings? The authorities are learning too, just like the population. How can we capture this two-sided learning process (with obvious strategic ingredients) ? These are critical questions, as they also to a large extent determine the dynamics of the epidemics, and are crucial to grasp how deconfinement should be implemented. And this is only a very small subset of the deep behavioural questions posed by emerging diseases.

References

- Almond and Mazumder (2005), « The 1918 Influenza Pandemic and Subsequent Health Outcomes: An Analysis of SIPP Data », American Economic Review P & P, 95, 258-262.

- Boucekkine, Desbordes and Latzer (2009), «How do epidemics induce behavioral changes?», Journal of Economic Growth, 14, 3, 233-264.

- Chakraborty, Papageorgiou and Sebastián (2010), “Diseases, Infection Dynamics and Development”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 57, 7, 859-872.

- Hirshleifer (1966), «Disaster and recovery: the Black Death in western Europe», Rand Corporation Memorandum.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Spring 2020 - Special edition on Covid-19 Crisis.