Emmanuelle Auriol, Julie Lassébie, Amma Panin, Eva Raiber, Paul Seabright, 2020, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135 (4), p.1799-1848.

What motivates religious believers to donate money to their religious organization? Do they give money in the hope of receiving insurance against economic shocks? In a recent paper, we examine how formal market-based insurance affects the demand for informal church-based insurance in Accra, Ghana. Specifically, we test whether people who are enrolled in a formal funeral insurance plan give more or less money to their church and to other charitable organizations.

We study the relationship between donations to religious organizations and insurance by conducting an experiment with church members from different branches of a well-established Pentecostal denomination. Pentecostalism represents one of the fastestgrowing segments of global Christianity, and Sub-Saharan Africa is a major Pentecostal center. Estimates from 2015 suggest that almost 40% of the continent’s Christians identify as Pentecostal or Charismatic. One important feature of Pentecostalism is the direct relationship between giving to God and material well-being. Pentecostal preachers speak of “a God who does not want His people to be poor or to suffer”. This mandate is often described as a variant of the “Prosperity Gospel”, the set of teachings claiming that “Christianity has to do with success, wealth, and status”. Pastors emphasize how behaving in a certain manner helps to avoid the risks that may impede success. Their preaching makes a strong and explicit link between giving to God and insurance.

Giving to the church might interact with the use of the church as an insurer in different ways. Individuals might donate because they expect the church, as an institution, to disburse funds in times of need. Or, individuals might use public giving to signal to other church members that they are good community members and expect other church members to help them in times of need. These two types of community-based insurance can be considered “material” insurance. From another perspective, the church is viewed by its members not only as a social network, but also as a setting for encounters with the divine. The church might therefore facilitate access to an interventionist god who can prevent negative shocks and favor positive ones. Church members might make donations to the church with the expectation of being protected from negative shocks. We call this a “spiritual” insurance mechanism.

To investigate which of the motives play a role in religious charitable giving, we conducted a labin-the-field experiment in Accra, Ghana. We randomly enrolled some church members for free in standard funeral insurance. The policy covered the participant and one of their family members for one year and paid out an equivalent of around 240€ (in 2015) to the family if a death occurred within the year. This provided us with two comparable groups of church members: one enrolled in insurance, and one informed about insurance but not enrolled. After the insurance enrollment, church members were asked to make decisions on donations equivalent to around half of their average daily income. In one round, they had to decide how much money to keep and how much to donate to their own church branch.

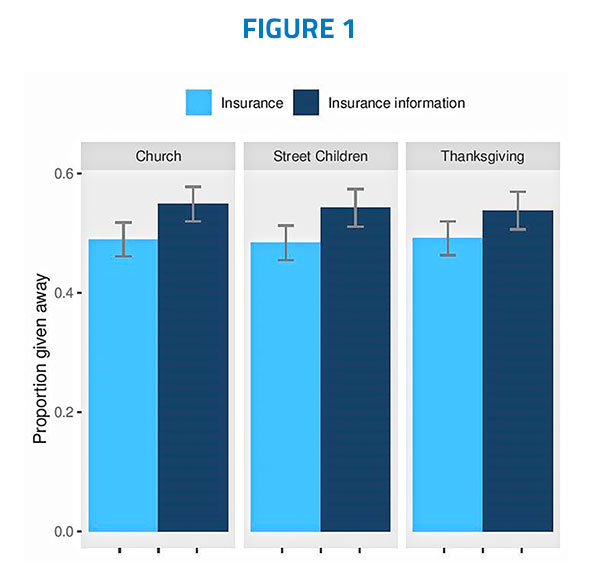

On average, the participants decided to donate 49% of the endowment. Comparing the two different groups, we find that those enrolled in insurance gave around 6% less to their church, a difference that is statistically significant (see figure 1).

To disentangle community-based and spiritual insurance, we also asked participants to make donation decisions involving two other recipients: the national thanksgiving offering and a charity that worked with street children.

While these recipients are unrelated to the participant’s own church, donations to them would be considered charitable actions and thus associated with the teaching on “giving to God”. Church members enrolled in the formal insurance also gave significantly less to the two other charities: the decrease in giving is similar for all three recipients (see figure 1). Church members changed their donations both to the church and to non-church charities in a manner that is consistent with a demand for divine protection and the spiritual insurance mechanism.

Our finding suggests that the previous literature on the interplay between religion and insurance might overstate the role of religious institutions as a provider of community-based financial insurance and understate the importance of a spiritual or psychological response to risk. However, 23% of church members who participated in our experiment reported having received financial help from their church at some point and 22% said they would ask the church community for financial help if they were in need. This suggests that material insurance from the church community is also important and we hypothesize that these two insurance channels co-exist.

© Photos by Ishmeal Lamptey on Unsplash & Eva Raiber

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Fall 2020.