Marion Dovis & Patricia Augier & Clémentine Sadania, 2021, Economic Development and Cultural Change, InPress

Part of the research was done while Clémentine Sadania was doing a PhD at AMSE under the supervision of Patricia Augier and Marion Dovis. Clémentine is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Mannheim

Research program

Strengthening youth skills by removing external barriers to schooling and reducing the need for early entry to the labor market is high on the agendas of inclusive development programs. To promote investment in the human capital of children and youths, it is vital to understand how external shocks affect their time allocation. The recent Egyptian uprising leading to the removal of President Hosni Mubarak on January 25, 2011 engendered a period of political instability that damaged the Egyptian economy. Workers were affected by this shock in different ways: for some, working conditions deteriorated, while others saw improvements to their job stability and earnings. This unusual setting provides the opportunity to simultaneously observe two opposite shocks on the father’s labor market.

From a theoretical point of view, the impacts of a change in the father’s income are uncertain. They may depend on a large number of factors and complex mechanisms. In particular, maternal bargaining power may affect the transmission of these shocks through the mother’s influence in household reallocation decisions, thus constituting another important determinant of the time allocation of children and youths. In this study, we explore the correlation between a dual economic shock and youths’ time allocation, taking into account maternal bargaining power during the transmission of these shocks.

Paper’s contribution

We first explore how positive and negative shocks on fathers’ labor market conditions following the political regime reversal in Egypt affected 16–20-year-olds’ investment in human capital. Second, we study the association between maternal bargaining power and the transmission of these shocks. Mothers may wield some influence in resource reallocation decisions.

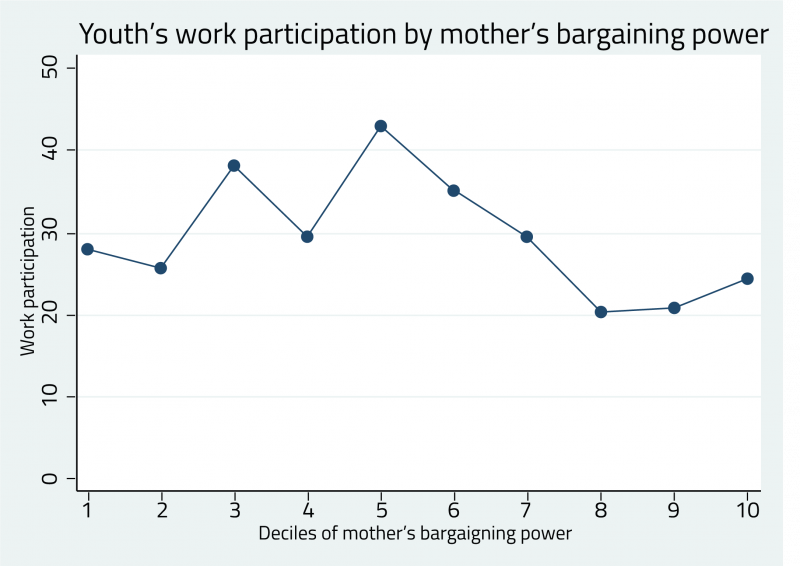

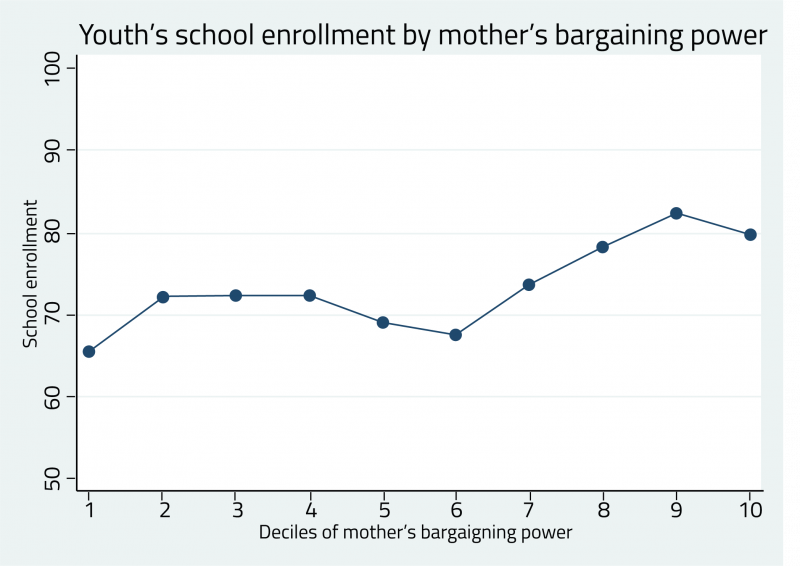

In our descriptive statistics, Figure 1, shows the youths’ time allocation according to their mother’s bargaining power estimated at the household level. Youths appear to be less likely to work and more likely to be enrolled in school when the mother has high bargaining power.

Focusing on the 16–20 age group allows us to capture major decisions: whether to enter secondary and tertiary education and whether to work. While schooling is almost universal up to age 15, school enrollment rates drop significantly after this age. Moreover, this age group is not as independent as might be expected. Unmarried youths remain at home and under the authority of their parents until marriage. Therefore, parental income and relative influence in household decisions have a major impact on youths’ investment in human capital. This is especially true for daughters: in the 2014 Survey of Young People in Egypt, 79.8% of 13–35-yearold married women reported that they were not autonomous in their decision on when and whom to marry, as compared with 45.9% of young married men. Household decision-making can therefore be expected to be correlated with the transmission of shocks to daughters’ time allocation.

The link between shocks and youths’ time allocation can be investigated in different ways. Our choice of model is based on assuming that decisions on work and schooling are neither independent nor ordered. We estimated the probabilities of these decisions simultaneously in bivariate probit regressions, taking reported changes in the father’s working conditions in the 2012 survey round of the ELMPS as the main measure of shocks.

Whatever the type of shock, positive or negative, we do not identify any significant correlation with schooling. However, we do find a negative association between the 16–20-year-olds’ probability of working and a positive change in their fathers’ working conditions, principally regarding daughters’ participation in domestic work. Interestingly, this effect holds only when maternal bargaining power is relatively high. Thus, daughters do less domestic work when fathers have a positive shock and mothers have high bargaining power. We find asymmetrical results in the effect of the father’s labor shock, with no significant association between a negative change and youth labor. This result is robust to alternative estimation procedures and other indicators of bargaining power. Our results suggest that maternal influence in household decisions allows the mother to direct new resources toward investment in her offsprings’ human capital when there is a positive shock on the father’s labor market.

Future research

We believe that the role maternal empowerment plays in shock transmission deserves further investigation. Future research should test this result in other contexts, examining whether the couple’s sharing out of household decisions is able to mitigate the role of negative shocks. A better understanding of the mechanisms at play would help to guide public policies so as to reduce impacts of external shocks on children’s and youths’ investment in human capital.

Figure 1. Youths’ time allocation, by mother’s bargaining power Calculations from authors based on the ELMPS-12

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Summer 2021.