Bruno Decreuse, Steeve Mongrain & Tanguy van Ypersele, 2022, Economic Inquiry, 60 (3), 1142-1163

RESEARCH PROGRAM

Quetelet, in the 19th century, had already identified the social science puzzle of a high degree of variance of crime rates across space. Recent studies suggest that this variance is not the result of observed or unobserved geographic attributes. Seeking to explain it, existing studies have so far focused on strategic complementarity between individuals engaging in criminal activities. We highlight a novel mechanism through which social interactions affect criminal outcomes. Households invest more in protection when their neighbors also invest in protection. This implies that private decisions have a social multiplier effect.

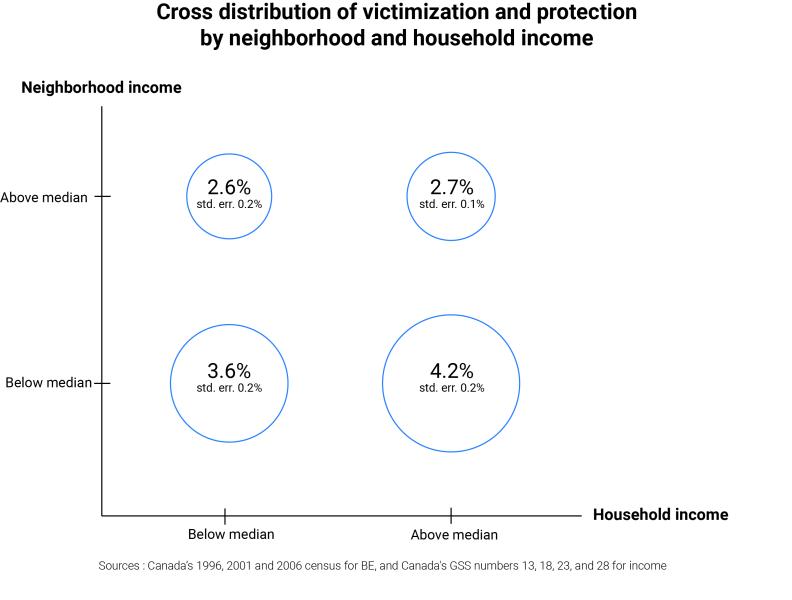

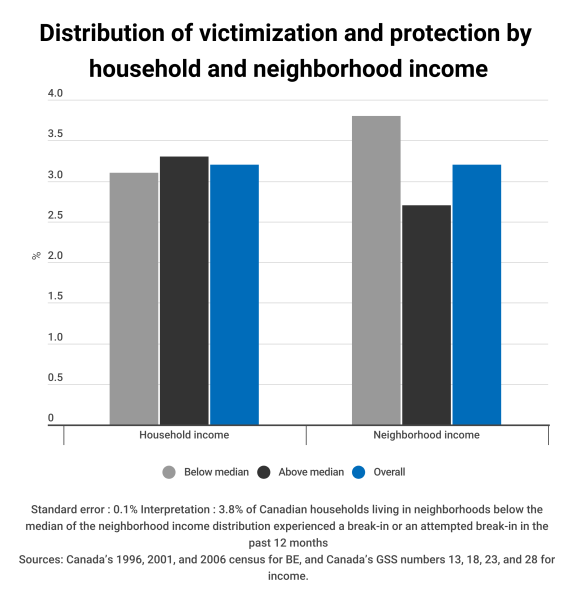

The paper presents four facts about victimization and protection investments based on detailed data from Canada’s General Social Survey (GSS). Victimization is measured by the share of the surveyed population who experienced a break-and-enter crime in their house during the year preceding the interview.

(i) Victimization and household income are uncorrelated or slightly positively correlated. Victimization is roughly the same for households below and above the median household income. (ii) Rich neighborhoods are victimized less than poor ones. The yearly mean victimization rate is about 3.4%, and neighborhoods below the median income experience victimization rates 35% higher than neighborhoods above the median income. (iii) Conditional on neighborhood income, rich households are victimized more than poor ones. (iv) Both rich households and rich neighborhoods invest more in protection. The percentage of households equipped with an alarm is about 30-35% higher among households above the median income than among households below the median income.

Basically, rich neighborhoods are less victimized but within a given neighborhood, it is the rich that are more victimized. Rich households and rich neighborhoods invest more in protection. To explain these facts, we provide a theory that builds on the strategic complementarity between criminal search effort and household investment in protection. There is a city composed of two neighborhoods, one rich and one poor. The supply of criminals is exogenous at city level, but arbitrage ensures that the returns on crime are equalized at the neighborhood level. Criminals also choose whether to pay a search cost to compare different households within the same neighborhood or simply to pick one randomly. Meanwhile, households invest in private protection to reduce losses from break-ins.

The two main mechanisms of the model are as follows. First, the criminals’ search implies that households make heterogeneous protection investments. Households who expect to be compared with each other invest in protection to divert criminals’ attention toward their neighbors. Second, protection heterogeneity motivates the criminals’ search. Thus, there is strategic complementarity between criminals’ search efforts and households’ protection investments.

Protection heterogeneity derives from the fact that protection is a positional good. Households make utility gains by being ranked higher in the distribution of protection investment. To see this, suppose that all households in a given neighborhood make the same protection investment, while some of the criminals pay the search cost to compare two randomly chosen households. Now, consider the case where two of the households are scrutinized by a given criminal. As they are alike, the probability of being broken into is one half for each of them. If one of these households were to invest more, the probability of being broken into would drop to zero and the marginal increase in effort would generate a mass gain. Therefore, similar agents make heterogeneous investments in equilibrium. Further, this argument implies that the distribution of protection investment has no mass point.

Our model can generate equilibrium outcomes in line with the above set of facts. In the absence of protection investment, the rich neighborhood is more attractive to criminals. However, its residents also invest more in protection, which deters criminals. Indeed, criminals in the rich neighborhood are more willing to pay the search cost than those in the poor neighborhood. Thus, rich households expect to be frequently compared with their neighbors. This affects both the mean (people invest more on average) and the dispersion of protection investments (there are still some people who choose not to invest, while others invest more). That the rich neighborhood invests more in protection implies low returns on crime, and therefore, criminals may be more attracted to the poor neighborhood. Meanwhile, rich households are victimized more than poorer ones in each neighborhood. This equilibrium allocation is illustrated by a parameterization broadly replicating the quantitative facts outlined above.

Importantly, the starting point of our analysis is that criminals are mobile between different neighborhoods of the same city. Everyone knows whether a neighborhood is wealthy or not, and criminals respond to incentives when deciding where to break in. In this light, the strength of our theory is its ability to predict the geography of crime despite criminals being mobile.

A large set of evidence suggests that crimes are most often committed near the criminal’s home, while criminals are more likely to be from lowerincome families (see, e.g., Burnett \& Tonkin, 2020). This is, in fact, compatible with our theory. The actual assumption we need is that criminals are sufficiently mobile between neighborhoods so that the return on crime is the same across neighborhoods. In our model, if, as is likely, more criminals reside in the poor neighborhood, then we can predict that most crime will occur near the criminals’ homes.

FURTHER RESEARCH

Our model can be enriched in a variety of ways. First, we assume that the number of criminals is exogenous at city level. This number could increase with the return on crime, and such an extension would allow us to study the impact of public policies aimed at reducing overall property crime. Second, we suppose that all agents are risk-neutral, whereas risk aversion is undoubtedly a key driver of protection investment. We could therefore study the resulting demand for insurance. Third, protection reduces losses inflicted on households by criminals. In addition, it could increase their probability of being caught. Fourth, we abstract from households’ residential choices. These should respond to the geography of property crime. Lastly, we make extensive use of Canadian evidence. It would be interesting to know whether similar facts hold in the US or in Europe.

→ This article was issued in AMSE Newletter, Winter 2023.

© punghi / Adobe Stock